Annemarie Strassel

Black is the new black.

Or, how I learned to stop worrying and love the uniform.

By Annemarie Strassel

The question of what to wear is at once frivolous and fundamental. Each day we all are faced with a decision of how to dress our bodies.

For over 200 years, men have had a formula for what to wear to work: the suit. Always in fashion, the suit embodies decorum and modernity. It has given men a clear roadmap for how to command respect at work and beyond.

For women, the choice has never been that clear. Faced instead with a dizzying array of possibilities, women are constantly reinventing themselves at work. The “freedom to choose” comes at considerable expense, time and effort. Moreover, in a world where women too often are valued for their looks above all else, we face constant scrutiny for these choices.

While acting as Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton was grilled by the media about her helmet hair, pantsuits, and weight gain. On the other side of the political spectrum, we have Sarah Palin, the former pageant queen, who was ridiculed and eroticized for her overtly feminine, perfectly coiffed political persona.

Clinton’s and Palin’s cases demonstrate that when it comes to getting dressed, women are caught in a double bind. Downplay your looks and be castigated. Embrace fashion and be dismissed. Both options frame women as ill-suited, literally and figuratively, for positions of prominence. Embedded in this scrutiny is a deeply cynical question: How can you govern others if you can’t even properly dress yourself? Our freedom to choose is a false freedom.

Of course individuality in dress is also a function of privilege. Millions of women worldwide don’t have a choice of what to wear to work. Occupational uniforms are typically assigned to underpaid workers in the service industry, and it is a myth that these garments are entirely functional. If that were true, why must so many women who work as hotel housekeepers clean rooms in dresses? In many workplaces, uniforms function to make labor conspicuous while making the individual invisible. They separate the work of the body from that of the brain. They make visible subservience while subordinating personhood to a broader corporate brand or institutional identity.

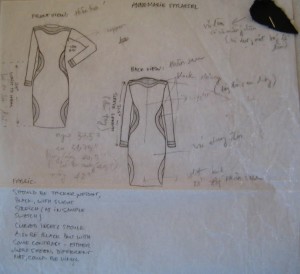

For me, the dress that Jamie Hayes has designed for me fulfills a longtime dream to reclaim the uniform as a vehicle for liberation rather than servility. I juggle multiple careers—design historian, media specialist for a labor union and college instructor—but I want my wardrobe to be simple. What if I could wake up everyday and not have to worry about what to wear? What if I had one garment in my closet that made me feel edgy yet professionally appropriate? What if it carried me from day to night, required no mixing and matching, and freed me from the tyranny of separates? What if that outfit was durable (structurally and aesthetically), hid dirt and never needed ironing? How much time, money and agony would I save?

The math is startling. Let’s say I saved as little as 15 minutes a day from deciding what to wear and 10 hours a month shopping and ironing. I would reclaim 923,250 minutes over the course of my life. That’s 15,388 hours. 641 days. What more could I accomplish if I had that time back? How much more closet space and money would I save? In a world of fast fashion and disposable separates, how much more could I reduce my material imprint on the world?

Historically, the color black has been my one salvation in a sea of choices—the one immutable, simple and carefree component of my wardrobe. It’s chic. Dirt-resistant. Professional. Figure flattering. What more could I want? All other ensemble items—shoes, tights and undergarments—can be made available in black in many sizes and styles, making it easy to pair and easy to purchase. Black is my staple. Imagine my disdain when gray became the new black, followed by navy, brown, white and then prints, of all things. Can we ladies have nothing that we can hold on to that is good and true?

Hayes has made for me a dress that fulfills my minimalist fantasy. It uses black masterfully, embracing its complexities by layering satin and sueded finishes to produce a look that is simple without being boring. In so doing, her design symbolizes the promise of austerity without compromise. It represents a freedom from false choices and the material burden of beauty culture, without rejecting a desire for beauty. It is the fulfillment of a dream and—now—the beginning of an experiment of a life in uniform.

Bio Annemarie Strassel teaches in the Fashion Studies Department at Columbia College and is a media strategist with UNITE HERE, a union representing 250,000 hospitality workers across North America. She received her Ph.D. in American Studies from Yale University in 2008, and is presently writing a book on feminism and American fashion.